|

|||||

|

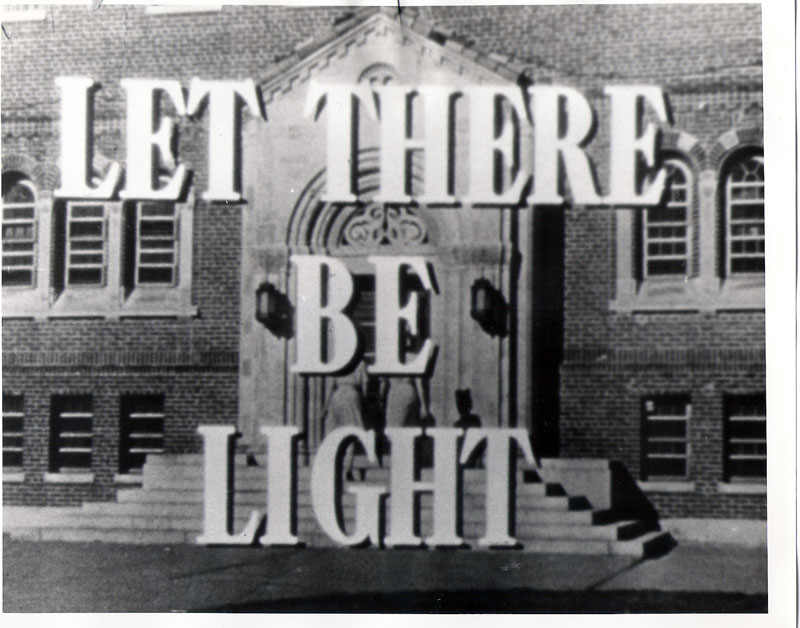

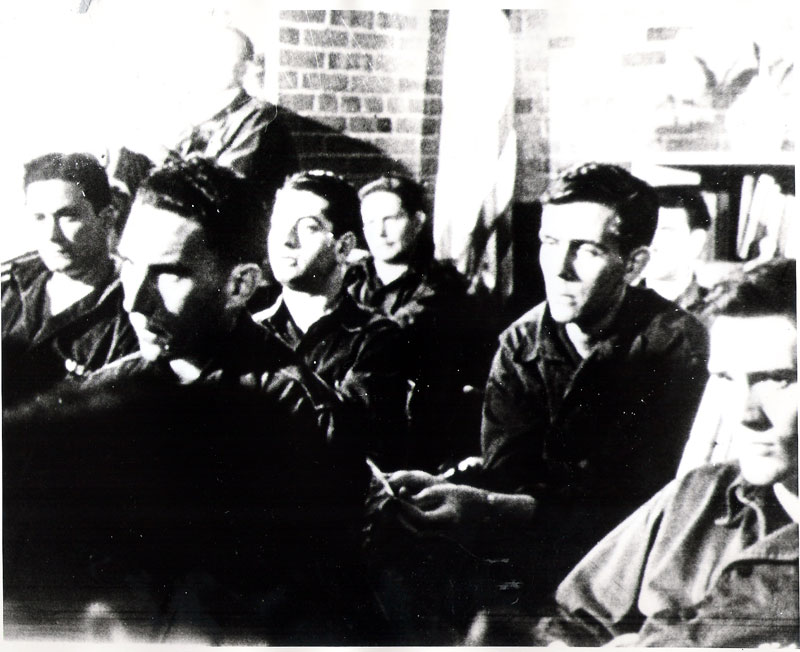

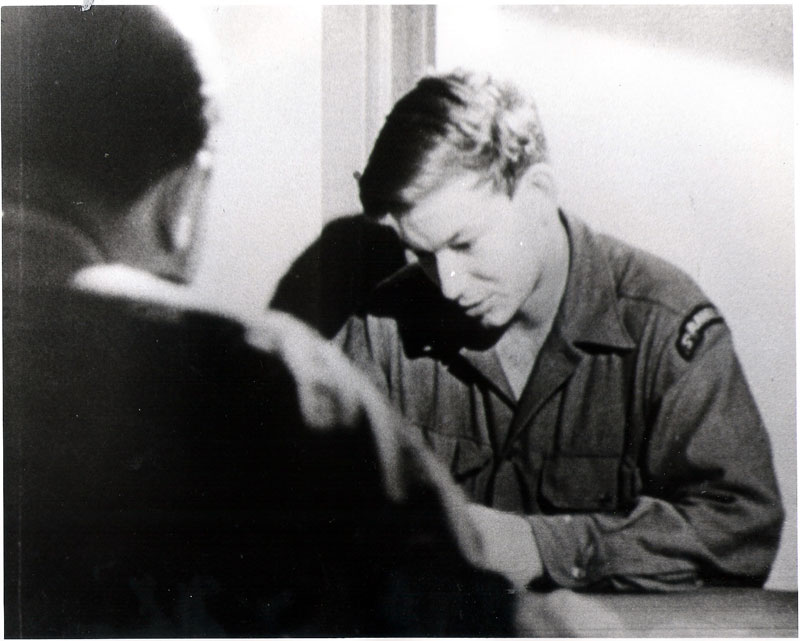

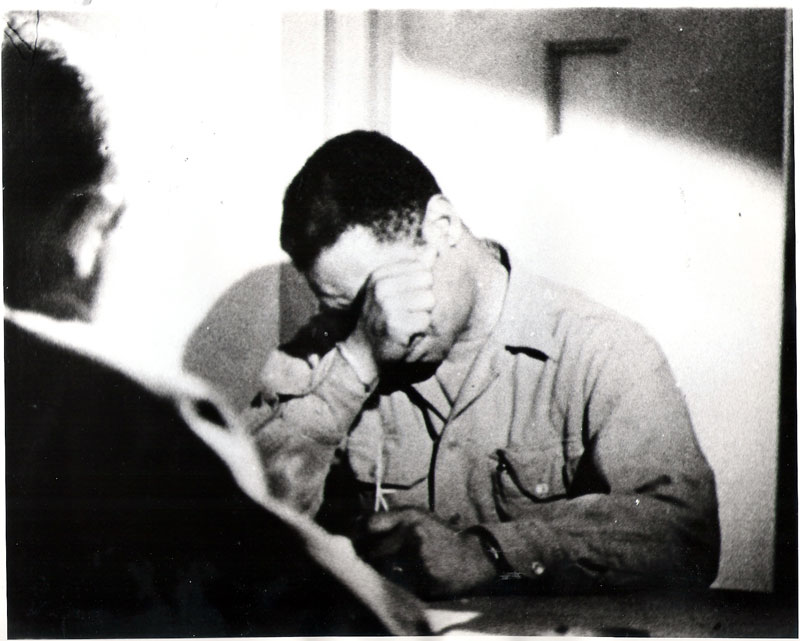

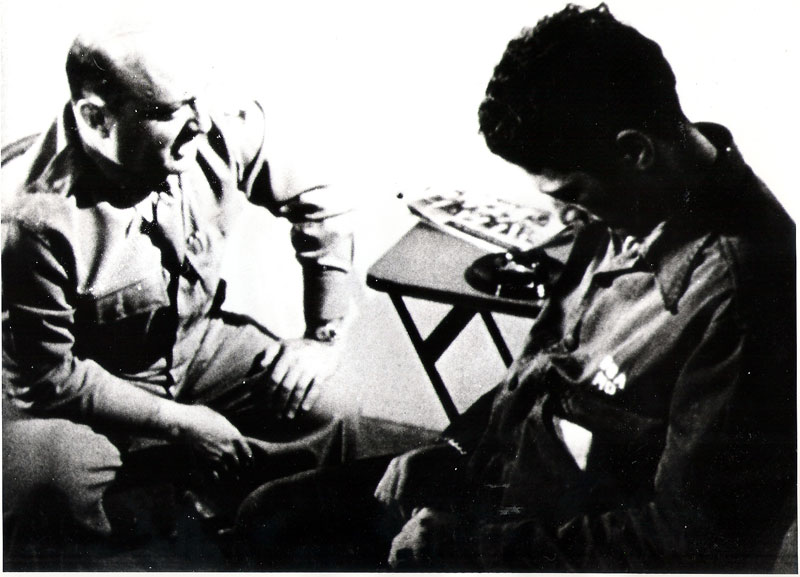

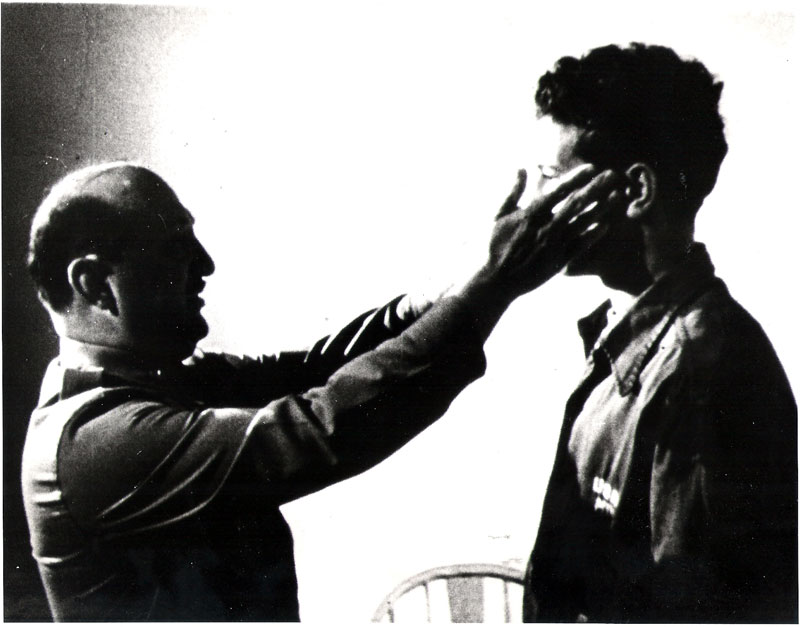

Let There Be Light "'LET THERE BE LIGHT," U. S. Army Film (Professional Medical Film) PMF 5019, was filmed in the spring of 1945. The crew included: Director, Major John Huston; Assistant Director, T/5 Morton D. Lewis; Writer/Project Officer, Captain Charles A. Kaufman; Editor, Captain Eric Lawrence; six cameramen, six electricians and two soundmen, one of whom was SGT Edward H. Dreyer. The film was narrated by Walter Huston. Technical adviser was Dr. Benjamin Simon, Clinical Director of the Connecticut State Hospital and a member of the Committee on Occupational Therapy of the American Psychiatric Association. Mason General Hospital, featured in John Huston's classic film about shell-shocked GIs is gone now, but a new web site is looking for photos: "I am looking for pictures of Mason General Hospital. The exterior of Mason was shown briefly during John Huston's film, Let There Be Light. The history of Mason is lengthy, and I will not get into it here. Please see www.edgewoodhospital.com if you want to read the whole story. If anyone can assist me in finding more pictures of Mason, please contact me at admin@edgewoodhospital.com." The film was the third of a series on the returning soldier: 1) average, 2) physically wounded, and 3) nervously wounded.Life Magazine featured an article on the film subject, using frames from the film as illustrations. Harper's Bazaar Associate Editor Dorothy Wheelock, requesting assistance at the time while preparing a magazine article, wrote: "We think the film one of the most important documentaries we have ever seen." The film was categorized as "Restricted" and eventually marked "obsolete." It was unavailable for public viewing for some 35 years until requests from Motion Picture Association of America President Jack Valenti and other Hollywood leaders persuaded the Army to release an edited version in 1981. The reason for the restriction was a cause for some speculation over the years. The original film clearly identified the GIs who were undergoing treatment. Releases were obtained, but the story was that the releases subsequently went missing. Another speculation was that the Army was worried that releases signed by individuals undergoing psychiatric treatment might not stand up to a challenge. And also, regardless of any legal protection, there may have been some real concern about exposing these wounded soldiers to public view and possible criticism. The film's dramatic lighting and impressive camerawork, with smooth dolly shots that looked like studio work, set a standard for documentary work. The powerful script suited Walter Huston's narrative style. In a series of interviews, the GIs reveal the basis of their individual symptoms, severe depression, stuttering, paralysis. "Death and the fear of death," pushed men beyond their capacity and translated into physical symptoms. In treatment that combined group therapy and hypnosis, several patients are shown dramatically overcoming their symptoms. The story brings hope for treatment and recovery of what we call now post-traumatic-stress syndrome, but it also ended on a sad note for viewers familiar with this problem. As a bus takes the recovered soldiers back to their civilian lives, the camera pans to a sad group of patients waving goodbye. Some of these patients never recovered. Frames from the film:

|

| ||||