|

|

Bill Ricks Bill Ricks [w.a.ricks@gmail.com] wrote: I dug out an old picture album, and I have a 5x7 b&W print of the studio building showing four cars in front. Window air conditioners at the third floor.

Scroll down to see Bill Ricks' collection of 1967 photos of APC.

Like many of the soldiers who served at APC, Ricks also had his overseas' tour. He sent this photo from his time in Vietnam:

(Posted August 14, 2006; updated August 5, 2018.)

|

|

William A. (Bill) Ricks provided these 1967 views from his collection of color slides:

A view of the main studio. My main work area was at one of the visible windows at left. I think it was second floor. We maintained and checked out cameras and other equipment. Also we worked with photographic instrumentation. I recall cannibalizing electronic assemblies.

Front of APC main studio at night, from barracks building window. That center entry opens directly onto the main stage.

APC barracks building across the street from the studio. I bunked at the far end, third floor. A TV room and food/beverage area was in the basement.

Parking lot behind the barracks. The back door of the mess hall opened on the parking lot, but this is a higher view.

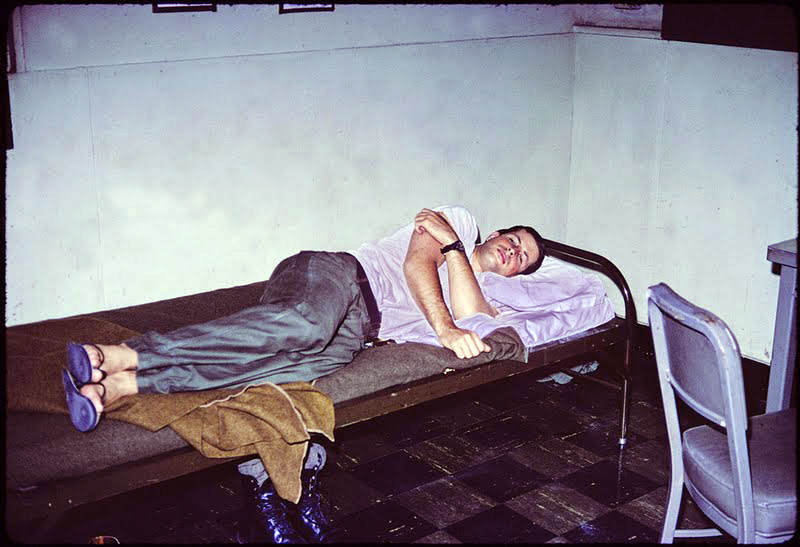

I'm sorry, I can't remember the name. This was typical view of the barracks.

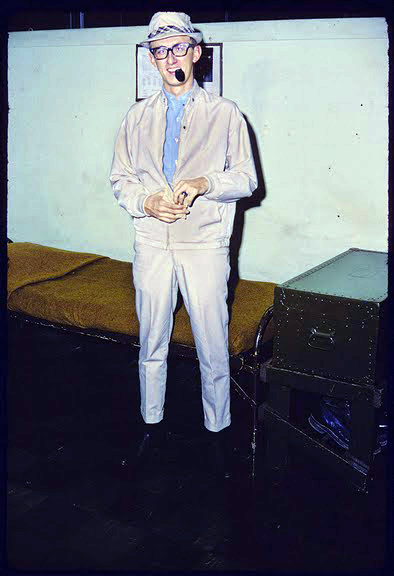

My friend Jim Walch, who worked in personnel. He was able to maneuver the timing of my 30-day leave. It resulted in my landing in Vietnam as Tet was winding up instead of being in the middle of it.

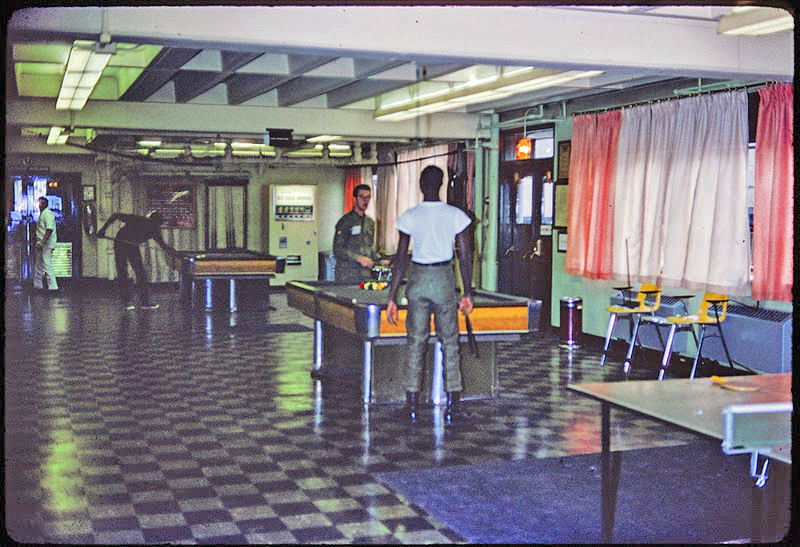

Game room. One of the career soldiers would walk in the room in a booming voice, saying "Piece of the action. Best in the house."

(Posted November 3, 2010; updated August 5, 2018.; updated February 4-6, 2019.) |

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

|

Updated February 7, 2019. |

|||

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

| Updated February 7, 2019. | |||

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

| Updated February 7, 2019. | |||

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

| Updated February 7, 2019. | |||

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

|

|

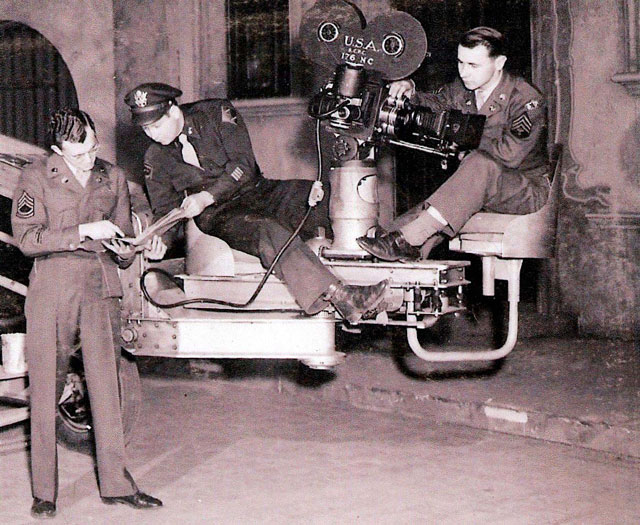

What Was APC/SCPC? At the start of World War II, the U. S. Army acquired a defunct motion picture studio at 35th Avenue and 35th Street in Astoria, Long Island City, Queens, New York, taking over in February 1942. The studio became the Signal Corps Photographic Center, later Army Pictorial Center, home to filmmakers and still photographers who covered the war and who produced countless training films.

The studio was built in 1919 as Famous Players-Lasky ("Famous Players in Famous Plays") to take advantage of the availability of talent on nearby Broadway and in the New York area. It was subsequently converted for sound pictures. As Paramount's east coast center, it was shuttered in the Depression. After serving as the Army's photographic center, studio and film library for 28 years, the Army Pictorial Center was ordered closed in 1970. The studio fell into disuse, but was subsequently sold and renovated as Kaufman Astoria Studios, now a production center for top filmmakers. About the name When it was established in 1942, the studio was designated by the Army as the Signal Corps Photographic Center. Later, it was called the Signal Corps Pictorial Center, and this is the title you see at the end of films like the Big Picture series. Finally it was called the Army Pictorial Center. The History The history of SCPC/APC is told in the Army's history of World War II. Here's an excerpt from "U. S. Army in World War II: The Technical Series: The Signal Corps: The Test," at page 390:

What was the Army post known first as Signal Corps Photographic Center and later as Army Pictorial Center? The center was a full service motion picture and still photographic production, distribution and storage facility with all the capabilities of any movie studio in the world. It was one of the answers to the military challenges of World War II. Army planners understood the need for training and propaganda material on an unprecedented scale. America had to convert hundreds of thousands of civilians into combat-ready soldiers and airmen, people from all walks of life, from all backgrounds and from all levels of education and skill. Reaching large audiences who represented widely varied levels of education and literacy meant using motion pictures and still photos. While it might be – and was -- possible to contract with existing film companies to produce training films, the Army saw a need to manage its own, dedicated studio where operations could be fully controlled and where sensitive or classified material could be prepared and stored with confidence. It may be difficult for people today to understand how different the culture was in the early 1940s. About 90 percent of the population went to the movies at least once a week. Commercial television was still years away, so movie newsreels and short subject supplied visual news and information. The Army saw the need to inform and educate the public about the threat the country faced and what the country was doing to meet that threat. The Army was also preparing to train hundreds of thousands of soldiers about a bewildering range of topics. These were people who were already familiar with the motion picture as an information source. The way to reach these vast audiences, of civilians and of GIs, was through the motion picture. And so, in May 1942, Army troops entered the former Paramount eastern services studio in Astoria, New York, and began preparing the place for work. Some of those G.I.s of 1942 stayed with the studio in peacetime. Sergeant Joseph J. Lipkowicz was with the SCPC unit when it marched in on the first day in 1942, and he retired as civilian chief of Camera Branch when it closed in 1970. Those who were there on that first day remember setting to work to clean out the place, throwing out old movie props and unneeded equipment to make way for the Army … which then spent the next three decades collecting its own unique set of props and equipment. Signal Corps Photographic Center became a home for many skilled individuals who served in World War II. Memories of soldiers indicate that a background or talent in film production or photography could be a ticket to assignment to SCPC. Personnel who served there ranged from well-known industry names like Frank Capra and John Huston to countless, uncredited GIs and civilians who made the place work. SCPC/APC had all the facilities of a complete movie studio. The main stage was the largest sound stage on the east coast, making it possible to prepare large sets or to construct multiple smaller sets for fast production. There were also smaller stages. Facilities included offices for writers and producers, a sound mixing room, screening rooms, animation and special effects departments, laboratory, library, and all the other elements needed to produce films. It was a one-stop shop for film production. The film and photographic library, the Army Motion Picture Depository, stored and distributed films produced by and for the Army. The library served as a single, central source for Army film. It held raw footage and combat film from around the world and, ultimately, from across three decades. It was the place where Army units could request training films. It was also the source where filmmakers, including civilian producers, could come to find documentary footage of Army operations. Distribution and control was simplified by concentrating on this single repository. The laboratory provided on-site processing, so handling, security, screening of daily footage was simplified. Soldier and civilian workers made SCPC/APC their home base while traveling around the world to cover Army activities. Combat cameramen shipped their footage to Astoria. People rotated in and out of the studio, going off to other assignments or to temporary duty, and then returning. Temporary duty – TDY – became a way of life as crews were shipped to Army camps and combat theaters to cover events and to shoot footage for Army productions. Those frequent travels remained a hallmark of life at the center. The studio always featured a mix of military and civilian personnel. The post was commanded by an Army colonel. During World War II, many of the talented filmmakers were experienced civilians who volunteered or had been drafted for military duty. Famous names of the era received officer’s commissions, like Lt. Col. Capra. Others served at lower ranks, like Pvt. William Saroyan. Troop Command supplied barracks for the soldiers. Former soldiers recall memories of SCPC troop units marching the city streets of Queens … after all, this was the Army. Bemused city residents would watch as soldiers blocked traffic at intersections to let the marching troops pass. Many others who worked there lived in the New York area, and many of those who started as G.I.s and stayed as civilians remained as residents in the region. The Army gained the same benefit from the studio’s location that former owner Paramount (and subsequent owner Kaufman Astoria Studios) enjoyed. New York offered a wealth of talent for film. Not only were actors readily available from the stage-film-radio-television scene of the city, but producers, directors, writers, cameramen, sound operators, and other skilled crew members were on call. The studio developed a dedicated staff of operational personnel who handled the less glamorous but necessary work needed to make films, such as lab technicians, film librarians, artists, printers, shipping clerks, and on and on. Films produced at the center met a wide range of needs. In the beginning, production was done in 35mm – mainly black and white, of course. Combat and field coverage – often shot with Eyemo and Filmo cameras – included both 35mm and 16mm footage. Distribution was often on 16mm film for showing in field conditions but also on 35mm for presentation in theaters. Later, color film became a staple, and field production began to rely on 16mm color negative, although 35mm remained the preferred stock for stage productions. While often recognized for training films that taught soldiers everything from personal hygiene to camouflage, the center produced, distributed and archived just about every kind of film, including the extensive archive of combat footage. In addition to training troops, films were made to influence civilian populations both at home and abroad. Franks Capra’s “Why We Fight” series gave American citizens understanding of World War II. In the Cold War era, “The Big Picture” told stories of history and current events to a national television audience. Training films used skilled actors, convincing sets and dramatic scripts to visualize the lessons being taught. The results were films that made a lasting impression on their G.I. audiences, illustrated by the many requests the studio received over the years from commanders who sought obsolete and long-retired titles that were so memorable from their own training days. Using its studio capabilities, the Army mounted everything from elaborate musical scenes to mundane office sets. On the main stage, you might find a field commander’s World War II tent or a Civil War battlefield. Combat coverage spanned three wars – World War II, Korea and Vietnam – with photographers and crews from the center travelling to all of the fighting fronts. During World War II, when air power was still the Army Air Force, combat camera crews brought back film of the air war as well as ground combat. While soldiers all around loaded and fired weapons, SCPC cameramen in those same foxholes would be changing film and capturing some of the most enduring pictures in history. The center was well equipped and made a point of keeping up with, and sometimes setting the trend for, new production techniques. Sound Branch converted from optical film to magnetic tape to mix sound tracks when the new technology became available. And that department pioneered the use of music-and-effects, or M&E, tracks, where the mix of sound tracks without dialogue or narration was recorded separately to allow revision of the voice track if needed. Special Effects, the mechanical and physical effects department, included such capabilities as rear projection, state of the art for that era. And that department pioneered the use of linked-focus cameras on copy stands, to shoot camera moves of flat art, an essential tool for a studio that used a lot of maps, titles and photos in its films. Animation could produce fully animated films. When the Army closed the studio, the Animation Department was still using an animation stand that had been built by soldier John Oxberry, whose Oxberry brand became the industry standard. Camera Branch stocked an extensive set of cameras, lenses, dollies, cranes and related equipment, including an assortment of then-industry-standard Mitchell 35mm cameras such as the studio standard BNC model. In later years, the center kept up with an industry trend and added Arriflex models. The studio also collected a surprising variety of antique equipment, items that were props, relics of early days or tools needed for a special job. For example, Sound Branch retained a disc recorder capable of playing the soundtrack records from Vitaphone days. Camera Branch held an extensive array of hand-cranked cameras – such as 35mm Universals, Pathes and others – from the silent film era. The films of APC/SCPC were quality productions, winning many awards over the years, including two Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awards – Oscars – and several other nominations. APC/SCPC was a unique, single-purpose facility that served the Army and the nation well, in time of wartime need and peacetime opportunity, to train soldiers and to inform civilians. It’s output of training and information films made a significant contribution to the speed of America’s response to world war after Pearl Harbor. The studio was the ultimate weapon in a war of mobilization and training, of information and ideas.

|

|

Posted February 8, 2019. |

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

|

||

|

APC

|

||

|

Updated February 8, 2019. |

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

|

||

|

APC

|

||

|

Updated February 8, 2019. |

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

Help Requested |

Personnel Roster |

Films |

Images |

Memories |

APC on the Web |

After APC |

Other Photo Units |

Books |

Contributors |

Search |

Contact |

|

|